Q and A, following online Vikalp screening of Narmada: A Valley Rises, May 2020

If you have missed the film you can watch it here

Vikalp@Prithvi is a monthly series of documentaries and short films brought to you by Vikalp: Films for Freedom in collaboration with Prithvi Theatre in Bombay. In May 2020, Vikalp@Prithvi programmed Narmada: A Valley Rises, viewers posted their questions online www.fb.com/VikalpAtPrithvi

Q. [Jayoo Patwardhan] My head hangs in shame. They just wiped out a whole natural culture and our heritage of an old way of life fiercely connected to its soil, plundered the most fertile Narmada basin all along those hundreds of miles, who will restore the plundering ? Is this what we believe in when we call something progress? Progress for who ? If these were landless adivasis and banvasis it’s written in the constitution that the fruits and crops of their land will be their property. And so my question is how can you call them landless. And if this land was not theirs it definitely did not belong to Gujarat govt ?

A. These are the kinds of questions that swirled through my mind when I first went to the valley and witnessed meetings held by Medha Patkar, in the villages of the incredibly fertile plains of Nimad as well as in the adivasi villages. Growing up in India two ideas were embedded in our education – Dams were the temples of modern India and that someone does have to pay the price of progress for the greater national good. Meeting the people who were being asked to pay the price of progress stripped away all the rhetoric embedded in these slogans which have become accepted as immutable truths. Also having lived in Canada, where the question of indigenous land rights is very alive, made me recognize that India is still administrated and governed by similar colonial era laws as is Canada. Colonial era laws have stripped away land rights from indigenous communities and this becomes glaringly evident when displacement looms on the horizon because of megaprojects. I don’t think things have shifted in past three decades for example, in 2019 the Supreme Court of India approved the forced eviction of a million tribal people from forested lands that they have lived in for generations. Not only has the Indian judiciary not questioned the underlying colonial, extractive intent of these 19th century laws it has continued to strengthen them by repeatedly declaring tribal people encroachers on their own land. This is the exact process that continues to happen in white settler states like Canada, Australia, New Zealand and of course the United States. My late friend Smitu Kothari, who was a key member of the NBA in the nineties used to say that the Indian state is carrying out a process of internal colonization – stripping away rights of tribal communities to their lands and sending the extracted resources to the urban areas.

I tried to capture the pain, anguish and anger of the affected people in the Narmada valley in film and I’m glad you were able to feel it.

Q. [Milan Acharjya] I have to know one thing through your eyes about the most influential factor, environmental costs of the Narmada Valley Project which was covered by the government. In your opinion what was the exact intention of government? Only for drought-prone Gujarat? Or else?

The Sardar Sarovar project was, and has been promoted from the outset as “the lifeline of Gujarat” and a key stated claim was that this was the ONLY option to bring water and relief to the drought prone areas of Kutchch and Saurashtra. These so-called benefits were going to reach theses area when the canal network was completed in 2025, this completion date is still far from reality. As activist, Amit Bhatnagar points out in the film the real beneficiaries were going to be the urban centres, industries as well as rich farmer growing water intensive cash crops such as sugarcane. My initial introduction to the story was through the eye-opening report done by the environmental group Kalpvriksh in 1984, which examined and enumerated the environmental costs and in doing so questioned the cost benefit analysis. One of the major contributions of the NBA has been to repeatedly ask fundamental questions that Medha Patkar clearly outlines in the film; who benefits and whose costs? where are these benefits going to go – to those who are more needy than others or to those who already have enough? Thirty years these questions not only remained unanswered in the “new India” but I feel they have been relegated even further to the margins.

Q.[Anckur Chaudhry] Considering you were also the cinematographer ( And had just 2 additional cinematographers. I would’ve imagined such a film needing at least 5-6 additional cinematographers.)… considering you also had to keep an eye on the narrative as the director. Honestly, that’s a quite a few considerations to consider 🙂 and yet none of these considerations / limitations seem to have limited the vision of your film.

Q.[Anita Parihar] What was the ratio of shooting done to the actual duration of the film .. and during the March which you meticulously covered .. how was your planning of shooting as per batteries .. ( there must have been moments when you may have found challenging to shoot at length – please explain how you shot the dialogue shots in as were you with a crew that was minimal or more ? I am eager to know the logistics of how you went about shooting at length …thanks.. this is a film that can be seen again and again and it’s nuances are further there to see!

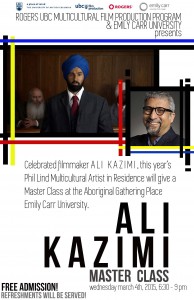

A. Ali Kazimi

Looking back, I was driven and inspired by the courage, strength and commitment of some of the most marginalized communities in India fearlessly asserting their democratic right to dissent in their quest for justice. I have always said that stories come to us as filmmakers, they choose us, and then it is our responsibility to bing them to life. Looking back at the film I often wonder how I did it all…it still amazes me.

To answer your question, I was the only one at the site. My friend and fellow filmmaker Himanshu Malhotra, documented the protests that were concurrently happening in Delhi; Anurag Singh documented the construction on the dam site, he went on to make his own film about the movement. (I inadvertently listed Husain Akbar, who did additional photography for a subsequent project.)

During the march I had an assistant, Naresh Kumar and a for a few days a sound recordist Ravi Sharma, most of the time I did the shooting and sound on my own; whenever possible Naresh also assisted with the boom microphone; sound is often more important than picture in a documentary, the fact that we were in a remote area with virtually no traffic or background noise helped in getting relatively clean sound.

I was trained in 16mm film but embraced video for documentary early on when it not fashionable to do so and when it was considered an inferior medium. The only way I could shoot this film to the highest professional standards and within my tiny budget was to try, the then recently introduced, Hi8 video format. In addition to the cost it had several additional advantages, the tapes were slightly larger than audio cassettes and they could record for an hour. I had budgeted to shoot 30 hours over 10 days, this was the anticipated time for the action by the NBA. Even with judicious use, I started running out of tape after the second week. Professional grade tape were impossible to find in India, I had an additional 30 tapes shipped from Toronto. These were stuck in customs, I had to make a quick trip to Delhi and Himanshu Malhotra helped me negotiate the customs process. It was miraculous; the customs officer was upset that the documentation listed video tapes, and he scolded us because as far as he could see on inspection these were ordinary audio cassettes! Charging batteries on location was a major issue, fortunately I had hired a Jeep for the duration and there were supporters in nearby towns where I could go to plug in my chargers for the night. I had also brought along a high capacity battery belt in addition to the camera batteries.

I returned in early ’93 to document scenics of the valley, life in the Bhilala villages and to interview the parents of Rehmal, the young man from Sunuur village who had been recently killed in a police firing; this time I was broke and shot this material on a consumer camcorder; the epic opening, title shot of the film in which the camera pans from the village of Domkhedi to reveal the Narmada was shot on this consumer camera.

As I often tell my students, I tend to be camera agnostic, I approach filming with any camera as I would with a high end film camera. I also subscribe to the adage that constraints are a necessary element to creativity. In this case I had to bring to bear all my training and experience to every moment, I must admit looking at the film now I am quite amazed at my 30-year old self who took on this challenge.

Wrestling nearly 70 hours of footage was the next challenge, there were dozens of possible ways of telling the story. I created a 9 hour assembly and then brought in one of my first mentors, Steve Weslak, whom I consider among the finest documentary editors anywhere to do the edit. We had 13 weeks, and we were cutting on a linear tape-to-tape system using U-matic (3/4 inch) worktapes. Unlike the digital realm of non-linear editing systems that are now the norm, tape based editing forces you to make nearly irreversible decisions in the moment.

Many hard decisions were made especially in terms of interviews, several key activists such as Chittaroopa Palit, Nandini Oza, Shripad Dharmadhikari, Himanshu Thakkar, Smitu Kothari, Lori Udall and Girishbhai Patel could not be included, even though they all played an important role in the movement, but ultimately as a filmmaker I feel I have to tell the best story possible while keeping the integrity of the events. This was my telling of the events as I saw them unfold. Indian Ocean founder/member, Rahul Ram, who was there on the march wrote a rich and wonderful account from his perspective in the newsletter of Kalpavrisksh.

Q) [Amira Lalani]I am eager to know the logistics of how you went about shooting at length …thanks.. this is a film that can be seen again and again and it’s nuances are further there to see! In a documentary it is equally important to show both the worlds for our rational mind to come with its conclusion.

I want to understand- For a documentary filmmaker how was it possible to get the consent of the pro dam supporters (like the chambers of commerce, Harivallabh Parekh.) For them to speak up. Weren’t they apprehensive or saw you as a threat?

A) It is hard to translate the fear mongering that was mobilized by the Gujarat government at the time; in the film veteran Gandhian Chuni Vaidya rationalizes the massive police mobilization as a “preventive measure” because he argues some felt the protestors were going to “break the dam”. The Gujarat-Madhya Pradesh border, usually of little consequence for road traffic, turned into a police led blockade. Soon after the march started on Dec 26, the Chief Minister of Gujarat and his entire cabinet organized a mammoth rally near the border, I was warned that it would be impossible to get access to film this event. When the march was one day away, I offered to go to Vadodara in the rented vehicle to send updates via fax to national and international supporters, I took the crew with me in case we happened to see something. On our way back we encountered the kitchen being set up by the Swami Narayan sect, I introduced myself as a freelance journalist and they welcomed us inside, showing off their preparations. One of the organizers became suspicious towards the end, they insisted that we must have some tea before we left. As we sat sipping tea, a professional photographer was brought in and set about photographing us, we in turn held the cups close to our faces to frustrate him.

I was feeling uneasy when we left and my fears were confirmed soon after; we rounded a curve on the road and a scene out of a B-movie unfolded in front in front of us. A platoon of cops swung into action, a newly setup barricade was hurriedly lowered, and to ensure that we did not smash thru it policemen rolled large oil drums onto the road. A visibly frightened driver brought our vehicle to a halt, and it was immediately swarmed by very aggressive police officers. While one demanded the papers for the vehicle from the driver, another told us that since we had been deemed to be with the NBA we were going to be arrested. At this point I asked Ravi who always wore a suit and tie, to go and talk to the the senior officers. Ravi assured me that he had encountered worse situations in riot hit areas, he had a press accreditation card, and assured me that he could handle it. The rest of us were forced to sit in the car surrounded by policemen. A few minutes later Ravi returned looking very downcast and worried, he said we were in a lot of trouble, that we were going to be arrested. We were told to get out of the vehicle and were marched to an area behind a small building where a group of senior officers were gathered around a table covered with documents and maps. One of them looked at me and asked me my name, when I responded he said in Hindi, “He’s a Pakistani, throw him in jail”, “Who are you calling a Pakistani, I recall saying, I’m a freelance journalist from Delhi, a stringer for Doordarshan (the state run tv broadcaster). In 1990, phone communication with cities, let alone across the country were limited and difficult, I knew that they would have a difficult time cross checking, I also know we had done nothing wrong or illegal. We were asked to stand in the sun a short distance away; a couple of hours later the commanding officer was handed a walkie talkie and he walked away from us. On his return we were asked to leave with the warning that if we crossed into Gujarat again we would be arrested.

I would later learn that at another checkpoint the police had pulled the same stunt on a group of senior print journalists, among them was a veteran Manjeet Singh. The journalists had been furious and had managed to have a message sent to the Press Council of India, who in turn immediately issued a stern rebuke to the Gujarat police.

The sound recordist was quite shaken by this event and felt that he could lose his accreditation with the national broadcaster, I empathized with his position and his departure was a setback. The fact that Naresh, the camera assistant and I had decided to stay despite the police intimidation had the unintended impact of everyone on the march truly welcoming us, it cemented their trust in us. After the march was stopped at the border, only journalists were permitted free access to both sides; Manjeet Singh, and another young journalist Manosh Sakaria would ask me to accompany them whenever they were going to see what was happening on the Gujarat side. Each time the police would try to move towards me they would warn them off saying that I was with them and a fellow journalist. Both men were true to the ideals and principles of a free press being a critical part of a functioning democracy, and without their active support I would never have had the access. As the days went by, I gradually ventured across on my own, ensuring that Naresh would whisk all fully recorded tapes back to the camp where they were safely hidden. Each day things were different, sometimes I could go across without journalists as witnesses at other times I would be warned that I was not permitted, the uncertainty was stressful and I believe designed to demoralize.

Manjeet Singh died in a car accident and Manosh Skaria, tragically drowned while swimming in the Narmada, I am indebted to them both not just for assuring that I had access to the Gujarat side but for also showing me first hand what committed journalists are meant to do in a democracy – witness, document and report to shed light on issues that go to the core of the democratic process, in this case the very right to dissent.

I approached the Chuni Vaidya, Harivallabh Parekh and asked them for an interview, I was upfront and told them that I was giving them an opportunity to present their side of the story, it took several tries but they eventually did agree.

Q)[Amria Lalani] You also continued staying day and night during the protest and fasting. When Medha Patkar was about to be taken to jail in an attempt to suicide. Did none of the officials targeted your team or tried stopping you when they saw the cameras? Maybe if you can take us through your challenges during that time.

A) I happened to be away filming at the resettlement in Malu and returned after dark just as the police arrived to arrest Medha and others. I gave Naresh the battery powered light and asked him to stay a few feet ahead of me to one side. It was pitch dark, and the first time I called out for him to switch on the light the police officers were shocked. They came at night because they knew that all reporters would have left, they could do as they pleased. I was deeply moved when groups of women surrounded me, both hiding me and my camera and protecting me, urging me to continue shooting; they recognized the importance of the camera as a witness as did the police, I grabbed as many shots as I could safely and then slipped away into the shadows. The officers ordered their men to look for me but no one would let the police pass.

3) Documentaries go on with uncertainty, no-one knows how long the journey will be. How do you decided and make the decision of where you need to stop and how does the finances part work here.

I left the day the indefinite fast ended, I had run out of money and my rented equipment was three weeks overdue. I knew that the chronology of the march and the standoff at the interstate border offered a perfect scaffolding for the structure of the film, what I did not have were the visuals of the valley etc.

By the time I returned to Canada, the first Iraq war was in full swing and no one was interested in hearing about a non-violent struggle in a remote part of India. Someone mentioned that I might want to approach the United Church of Canada which is known for supporting progressive causes, surprisingly they not only returned my call but they were up to date about the struggle in the Valley. I received a small but critically important grant from them with no strings attached. Documentary film production in Canada is supported through grants from various levels of arts councils in this case – the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council and the Toronto Arts Council but all these grants collectively are never enough to pay for professional fees and services. I knew that I had to try to achieve the highest technical standards in post-production. In order to access funds from the federal funding agency, Telefilm Canada, one needed a letter of commitment from a national broadcaster to show the film in prime time (7pm-10pm). Again with the help of the incomparable Steve Weslak, I cut a 15 minute demo, which proved to be invaluable. The only broadcaster to step in was a multi-faith channel called Vision TV and based on their letter I was able to leverage funds from Telefilm Canada. It took three and a half years, made for frugal living, and it was stunning to experience first the selection of the film for the Toronto International Film Festival and then the incredible response from the audience.

I could go on but hopefully you have a sense of the process.